There was nothing obviously notable about the LinkedIn announcement introducing Cisu Capital Partners to the world.

Cisu, named for the Finnish word “sisu,” which roughly translates to grit, is “excited about the opportunity set in global financial services and proud of the team of professionals we have assembled,” the post, from early August, said. The London-based manager, according to people close to it, will start with assets of $200 million to $300 million — a solid sum, but far from the largest the industry has seen.

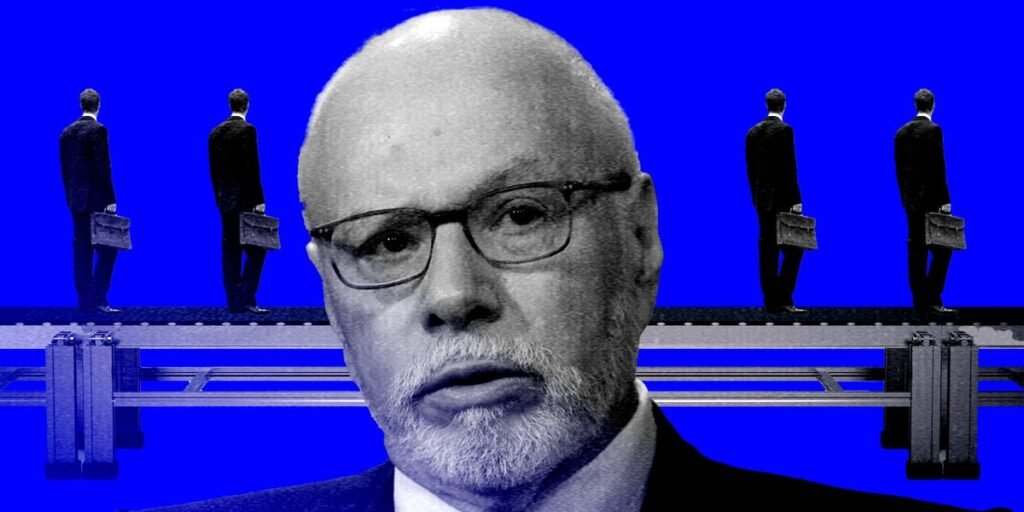

To outsiders, the most interesting fact about Cisu is its inclusion in a rapidly growing collection of new funds spread across the globe. These funds have different strategies, backers, and philosophies but share one trait: Their founders all worked at Paul Singer’s feared Elliott Management, the $69.7 billion hedge fund best known for its activist campaigns against blue-chip companies and foreign governments.

Cisu’s founder, Mark Wills, is the latest Elliott alum to spin off and start his own firm. At least nine ex-Elliott investors in the US and the UK have started their own funds over the past three years or are in the process of launching. In recent years, Elliott has also lost senior talent to various leadership positions across industries.

The explosion of Elliott alums starting their own firm’s and senior leaders leaving the manager was brought on by the fund’s across-the-board restructuring, six former and three current employees said.

The turnover at the 47-year-old firm is the latest example of the ripple effects of the increased institutionalization of the hedge-fund industry, where the biggest firms are mimicking peers in private equity.

Insiders say the firm has changed massively in recent years, culminating in the creation in 2020 of an all-powerful investment committee. The 15-person committee — which includes young partner Jesse Cohn; Singer’s son Gordon, the UK head; and Elliott’s No. 2, Jonathan Pollock — has helped turn the $69.7 billion firm into a more structured but also bureaucratic and political place, these insiders say.

“It used to be like a bunch of mercenaries,” one person said, where anyone could bring ideas to the heads of the firm and be rewarded. Now, there is a more set pecking order.

The evolution has led some longtime investors to strike out on their own, partly to regain the merit-driven freedom they felt Elliott had lost.

“The changes haven’t been in place for that long, but the firm is different now,” a former investor said. “It’s rigid.”

Elliott declined to comment.

The story continues below the table, which includes information from people close to different launches and executives as well as previously reported information.

Cogs over cowboys

Even those most frustrated by the infrastructure changes acknowledge that something needed to change.

A former investor said Elliott had attracted “a certain cowboy type of investor” throughout its history because it was one of the few hedge funds — if not the only — that let employees seek out opportunities regardless of asset class, geography, or strategy.

“The mandate,” another former investor said, “was go do something interesting, find something interesting, and if it fails you’re fired, but if it does well you’ll make a lot of money.”

It allowed for young, talented investors to rise in the ranks quickly — several people said 43-year-old Cohn’s meteoric rise to his role happened because the firm’s structure at the time allowed him to do so — but lacked the layers and controls, like an internal general counsel, that institutional investors like to see. As the firm got bigger and as senior leaders increasingly lacked time to get to everything, it needed more infrastructure and better firmwide communication.

Some people said it could take several weeks to get on Pollock’s schedule before the pandemic, meaning they’d struggle to get sign-off on time-sensitive investment opportunities. Now responsibilities have been delegated throughout the firm’s senior leadership.

However, the additional bureaucracy that came with the structure meant a departure from the eat-what-you-kill environment in which many of the firm’s veterans were raised. Several said this was how Cohn made his name in software investing early on, winning him the favor of Singer and others.

Former and current employees said new boundaries were drawn on investment strategies, putting people in more neatly defined boxes. These people said portfolio reviews from managers became more common, and it became more about “who is going to champion your idea” among the firm’s brass than who actually found the opportunity.

“There used to be two layers above — now there’s 10,” a former investor said. New hires are now placed under a specific portfolio manager with a more specialized field — such as real estate or distressed companies — to mine for opportunities and have a more prescribed career path.

The insiders described it as a Blackstone-like career progression: analyst for four or five years, associate portfolio manager for four or five years, and then, if all goes well, portfolio manager.

“It’s a much more top-down style where you work for the guy, who owns your idea, and he shares the idea with the guy above him, who owns it in a meeting, and so on and so on,” this person said.

Despite the departure of long-tenured portfolio managers, the firm’s investment head count has grown alongside its assets. The manager said in a regulatory filing in May that it had 238 people working in investment roles, a 27% jump from the end of 2020. Assets went from a little over $45 billion to $69.7 billion over the same time.

But several former employees argued that the additional people weren’t in the mold of those who came before them.

“For every cowboy investor they lost, they gained three bureaucrats,” one person said. “They are backfilling with cogs.”

Nowhere else to go

Why disgruntled Elliott veterans — several of whom said they’d planned to spend their entire careers at the firm before the structural changes — have largely turned to launching their own funds over joining competitors is pretty simple, several of them said: There’s no true competitor.

According to two recruiters, cold calls to Elliott talent are being returned for the first time in the firm’s history. But several tenured investors at the firm told BI that they wanted the freedom they once had at Elliott, not a new boss.

“There’s not many places to go to that replicate what Elliott is doing,” one longtime investor for the firm who’s no longer there said.

Senior PMs, for example, will have far fewer positions under their purview than peers working at multimanagers like Citadel or Millennium but still run more-varied books than specialized distressed shops or special-situations managers that home in on a few opportunities.

“Once you leave Elliott,” this person said, “you’re either setting up your own shop or you start doing something much different than what you were doing before.”

The founders’ reasons for starting their own businesses are, of course, different. Some wanted the ability to focus on smaller opportunities that Elliott had gotten too big to care about. Some were fed up with the firm’s politics and wanted a fresh start. Some felt stunted by the slower pace of promotions at Elliott, miffed by compensation decisions, or even pushed out of the firm.

“Nobody told us the deal changed,” one person who departed said.

“I feel like the ladder was pulled up,” another younger Elliott alum said.

But all have benefited from their shared history. It’s opened doors to backers who know Elliott as a unique place — an investor in one of the new launches said Elliott talent thinks about the world differently because Elliott is unlike any other fund. Longtime employees also have often had several big personal paydays that help get a new fund off the ground (and provide peace of mind in case of a flop).

The rash of launches, though, is also a case of employees realizing it’s possible. Unlike the large pod shops or the extended Tiger Management family tree, Elliott doesn’t have a long history of alums setting up their own funds.

Mark Brodsky, the secretive founder of Aurelius Capital Management, is the best-known spin-off, but his firm launched in 2006. Several people said the fundraising success of both senior PMs and younger investing talent over the past few years inspired others to launch or consider their options.

Several pointed to Adam Katz’s successful start at Irenic — where he’s now running more than $1 billion — as starting a chain reaction within the firm’s ranks of employees who had kept the idea of running their own fund in the back of their minds.

Not slowing Elliott down

Elliott, meanwhile, churns along. The firm made 4.5% in the first half this year and has had only two down years over its nearly half-century of investing.

The firm’s latest fundraise came in higher than originally reported, pulling in $8.5 billion in new capital that can be called at any time over the next two years, after an $11 billion raise in 2022. By comparison, this year’s largest fund launch — Bobby’s Jain highly anticipated new firm — raised $5.3 billion.

The reality for megafunds like Elliott is that additional structure is a selling point for their biggest investors, especially given the age of Elliott’s billionaire founder, who will be 80 this month. The firm’s competitive moat is that no one can do what it does at the scale it has.

“I don’t think anyone has been looking for a new version of Elliott because they know how hard it will be to build it,” a former trader said.

The firm still has the rapt attention of any boardroom it sets its sights on — after meeting with Elliott recently, Starbucks this week replaced its CEO with Chipotle’s CEO, Brian Niccol. Elliott has also launched a boardroom battle at Southwest Airlines.

Another selling point is the firm’s longevity across its senior ranks. A person close to Elliott said that the average member of the management and investment committees had been there for 21 years.

And there are still paths for promotions. The firm this year named three new partners — Nabeel Bhanji, Jason Genrich, and Marc Steinberg — and the person close to the manager stressed that Elliott is not and has never been a place where one person is the star.

Losing talented people is tough, but the machine won’t slow down.

A hedge fund as old as Elliott has survived in part because it has been able to replace employees. Its reputation, which has helped its former employees raise money and find new jobs, also attracts top people to the firm.

This year, the manager has poached Jordan Bryk from Marathon Asset Management to be a managing director for private credit in its New York office. Last year, it hired Centerbridge managing director Tim Denari to bolster its London team and hired Cornwall Capital partner Aaron Tai to focus on activist investments in Japan.

As one former employee put it, the firm’s mantra now seems to be “We have a name, we have a brand, we can backfill talent.”

But this won’t temper the nostalgia some of Elliott’s veterans have for the old days. One member of the older generation lamented the loss of what they termed the “Elliott mindset.”

“One of the strengths of Elliott people is that they did a little bit of everything,” this person said. “That’s not going to be the case anymore.”

They added, “You need to have smart people throughout the chain of command.”

Still, this person is an investor in the fund and said they don’t plan to redeem anytime soon.

Read the full article here